Posted on December 9th, 2025

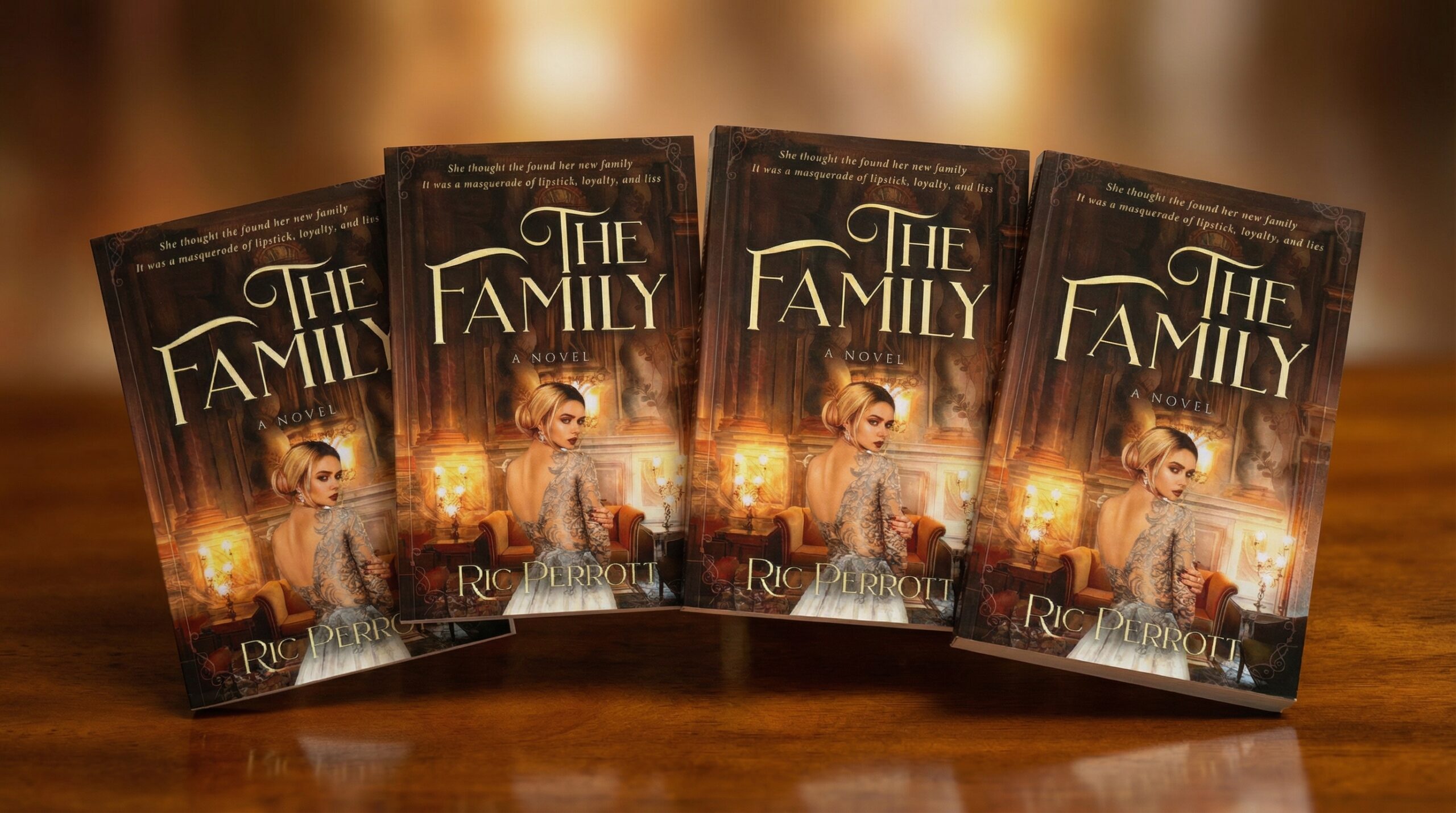

I’m posting this on the day that my debut novel releases to the world. Sitting here holding the finished product in my hands—the smooth texture of the glossy cover, the rough feel and intoxicating scent of the paper—I feel fortunate. This is a moment I’ve been thinking about for almost thirty years, and now I get to share it with all of you, which is pretty amazing. One question I’ve been asked by the folks who have read the book is, “Why this story?” It’s a fair question. This is an unconventional debut novel from someone like me, so I’d like to talk a little about why and how The Family came to be.

It all started with a stripper in a window.

I was twenty-six years old, walking down West 55th Street in Manhattan after a long day of coding (we called it programming back then), and I stopped at one of my favorite quick dinner spots: Blimpie. I’d always get the club—ham, turkey, swiss cheese—and top it with sweet peppers that were, in all truth, one of the most amazing things I’ve ever put in my mouth. An oversized cup of fruit punch rounded things out, and I had myself a complete meal for about five bucks. This became a routine.

Back in the mid-90s, New York City still had a little grit left to it. Giuliani hadn’t fully sanitized it yet, and there were remnants of the old Hell’s Kitchen lurking in the corners and alleyways. Like the inconspicuous strip club just off 8th Avenue on 55th Street—blink and you’d miss it. Made up of one nondescript door painted the color of dried blood, and one slightly askew, pink neon sign that buzzed and flickered with the rhythm of a dying heartbeat, casting salmon-colored shadows across the sidewalk. I’d walked past this place dozens of times, but on that particular night something told me to look up.

So I did.

Sitting halfway out of the fifth-floor window was a young woman, blonde and petite. She was sixty feet up, perched on that ledge with casual indifference, and smoking a cigarette with the slow, deliberate drags of someone with a lot on their mind. Even from street level I could tell she couldn’t have been older than twenty-one. Something about her fearlessness and the confident way she presented herself; the city hadn’t worn her down yet. The ember of her cigarette illuminated her face with each inhale. She noticed me looking and waved, her hand cutting through the ribbons of smoke that curled around her. I waved back, and she motioned down toward the door, a slight gesture of invitation. I declined, but something about her stayed with me: the way the night seemed to bend around her silhouette, the courage of that perch, the sad poetry of the girl framed by a window in a place like that.

Not even two weeks later, the same scenario played out. Long day. Blimpie club sandwich wrapped in an oversized bag. Turn the corner onto 55th. Look up out of habit, or maybe hope. And there she was again, same window, same cigarette. My memory could be romanticizing the exuberance of her wave that night, but it was definitely one of recognition. She’d remembered me. So I waved back, easier this time, and saw a smile break across her face as she pointed down to the street in another attempt to lure me into the den of ill repute. The pink neon buzzed its siren song, but once more, I declined and moved on.

I didn’t see her again for at least a month. But on a night when it was lightly raining—that fine mist that hangs in the air like static and turns the streetlights into watercolor halos—I crossed 8th Avenue, and caught, in my peripheral vision, the red glow of a cigarette ember in that fifth-floor window. It was her, though she didn’t see me this time. She was occupied with something inside, her silhouette turned away, framed by the dim amber light of the room behind her. As I walked home, collar up against the drizzle, I started creating a backstory for her. Where did she come from? Some small town with a water tower and a main street that rolled up at nine? How did she end up here, in this window, in this building, in this particular corner of the city’s vast indifference? Did she enjoy what she was doing, or did she feel trapped, counting the hours like a prisoner marking days on a cell wall? The questions followed me across town, as persistent as the rain.

The seeds of The Family were planted right there on that rain-slicked sidewalk. The rest of the story grew independently of her, of course, sprawling into something I could never have predicted. But without those chance encounters, without those questions, I don’t know if this story would exist.

I tried to write it as a movie first. Back then, I tried to make everything a movie first. I was taking screenwriting classes, and that’s where my creative brain naturally defaulted. The original concept was more action-thriller oriented than the novel ultimately turned out to be, but it carved out the initial roster of characters: Star, Melody, Caron, Sage. They were all born in those early writing sessions, fully formed and demanding attention.

The farthest I’d gotten was about seventy pages worth of screenplay. Most of the way through Act Two, but nowhere near close enough to stick the landing. This became a pattern—I’d work on it in spurts, hit the same wall, put it away, swear I was done with it, then come back to it to begin the spiral over again. One day, the inspiration wouldn’t come, so I filed it away and told myself I’d never go back to it.

Until I did.

When I took early retirement and committed to trying out long-form fiction, the story that eventually became The Family kept circling back, like it wanted to be finished. Like it needed to be. I’d sketch out what it could look like as a novel, how to explore Esther’s interiority and make it something worth getting lost in. And suddenly, it clicked. All the roadblocks and sticking points I’d hit in screenplay form smoothed out in prose. The relationships deepened, and the pacing found a rhythm. I spent a couple of months brainstorming and outlining, but once I started drafting, I finished the first in less than three months.

It was bloated at almost 140k words and the pacing was a mess, but it was finally a complete story, and felt more real than anything I’d written before.

Then came the hard part. Months of editing and revision. Entire chapters excised, scenes rearranged, dialogue rewritten, structure rebuilt until I had something I wasn’t embarrassed to show other people. From there, the usual gauntlet: feedback, revision, more feedback, more revision, until it eventually became the completed novel sitting on my desk. The old adage, of course, is that novels are never truly completed—they are abandoned. And I think that applies in this case as well. I hope I left it in a nice place, with a warm bed, and people that care.

I never saw the girl in the window again, and to this day I don’t know if she was more Star or more Melody, or maybe even more Sage. But I know she’s the reason this story exists. Asking those questions led to answers that only raised more questions, which demanded more answers, and eventually it became something. Completing this novel is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done in my life, and if you’d seen some codebases I’d worked on, that statement would be far more impressive than it seems right now.

I’m very proud of The Family, and I hope that if you choose to read it, you can share a bit of Esther’s world, and live in her messy head for a while. And maybe, when you’re done, you can picture her sitting in that fifth-floor window, waving down at a tall, goofy guy with a Blimpie bag who still thinks about her and wonders what she might be up to.

Thanks for reading.